BBC News

BBC

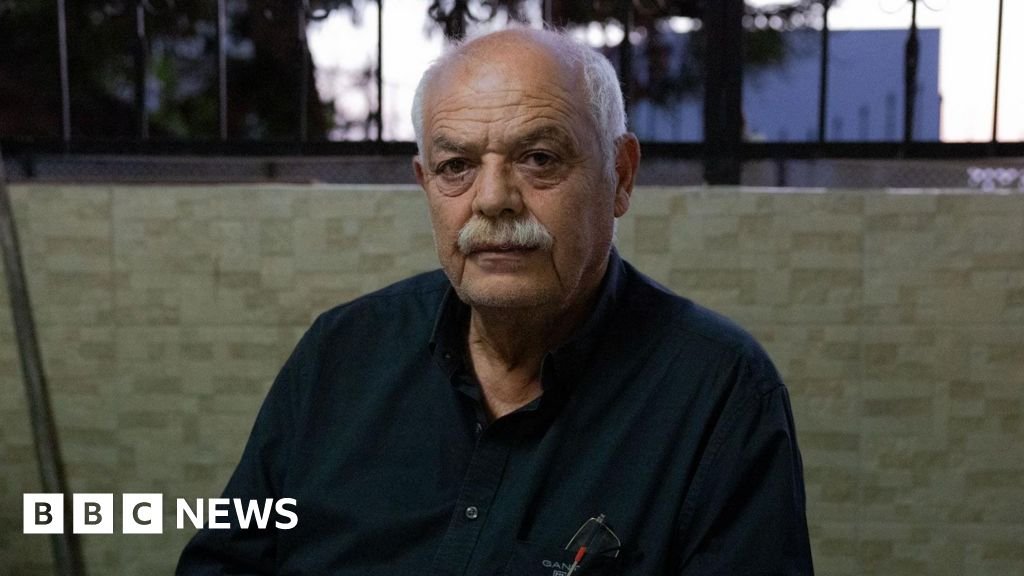

BBC“I am so angry,” says Kasem Abu al-Hija, 67.

On Saturday, four of his family members were killed when an Iranian missile struck their home in northern Israel, collapsing the concrete building on top of them.

Books, clothes, children’s toys and body parts were blown into the road, witnesses say.

The whole street was plunged into darkness when the missile hit. Rescuers managed to locate their bodies by following trails of blood.

The four victims were named as Kasem’s daughter Manar Khatib, 45, his two granddaughters, Shada, 20 and Hala, 13, and their aunt, Manal Khatib, 41.

They had managed to make it to the two reinforced safe rooms in the house that they shared – but the ballistic missile hit it directly.

They lived in Tamra, an Arab-majority town in northern Israel.

Minutes after their deaths, a video emerged online. It showed the Iranian missiles streaking through the sky overhead. As they descend on Tamra, a voice can be heard shouting, in Hebrew: “On the village, on the village.”

“May your village burn,” a group of others then say, singing, whooping and clapping.

“They sang about what happened to my family,” says Kasem, softly, surrounded by relatives at a vigil.

The video – which shows Israelis singing a common anti-Arab chant often sung by ultranationalist Jews – has been widely condemned in Israel, with President Isaac Herzog calling it “appalling and disgraceful”.

But there are more reasons that Kasem and the wider community in Tamra are angry about what happened.

Here – as is the case with many Arab-majority communities in Israel – there are no public bomb shelters for its 38,000 residents.

For comparison, the nearby Jewish-majority town Karmiel, population 55,000, has 126 public shelters.

Residents of Tamra have long raised the alarm over the disparity. Situated in Israel’s north, about 10km (6 miles) east of the city of Haifa and 25km (16 miles) south of the border with Lebanon, the town has been vulnerable to rockets fired by the Iran-backed Lebanese group Hezbollah. In October 2024, a rocket fired by the group seriously injured one woman.

Across Israel, about a quarter of the population have no access to a proper shelter. But in non-Jewish local authorities the figure is almost half, according to a 2018 report by Israel’s State Comptroller, the most recent data available.

“For many decades, Arab local authorities have received lower state funding across various areas, including emergency preparedness,” says Lital Piller of the Israel Democracy Institute, a think tank.

Where shelters do exist, she says, “they are few, poorly maintained, and often not suited for prolonged stays”.

The BBC has approached Israel’s Ministry of Defense for comment.

Israeli Arabs – many of whom prefer to be called Palestinian citizens of Israel – make up a fifth of the country’s population. By law, they have equal rights with Jewish citizens, but they routinely complain of state discrimination and being treated as second-class citizens.

Following the Gulf War of 1990-91, when Iraqi missiles hit Tel Aviv and Haifa, the Israeli government mandated that all new residential buildings must contain a reinforced safe room, or Mamad, as they are known.

But Arab communities often face tough planning restrictions, which leads to unregulated construction and homes being built without them, activists say.

About 40% of Tamra’s homes have their own safe room, local authorities say, leaving the majority of residents having to run to neighbours’ homes to share. In many cases, due to the short warning period, this is not possible.

“The gaps are enormous,” says Ilan Amit, of the Arab-Jewish Center for Empowerment, Equality, and Cooperation (Ajeec), which works to build shelters in Arab communities. “I live in Jerusalem. Every building has a bomb shelter. Every neighbourhood has a public bomb shelter.”

As dark falls in Tamra, residents’ phones light up simultaneously with a screeching alert: “You must stay near a protected area.”

Sirens soon follow, and residents – fresh from the trauma of Saturday’s strike – panic. Mothers gather their children and people run up the street shouting. Several families cram into the safe room of one house. Some cry, some smile, others twitch nervously. One man closes his eyes and prays. Boom after boom is heard overhead.

The shelter issue is even more pronounced in Israel’s Arab bedouin communities – many of which live in villages in the Negev Desert that are not recognised by the Israeli government, so do not have shelters built for them.

The only victim of the April 2024 escalation in hostilities between Israel and Iran was a young girl from one such community who was seriously injured and spent a year in hospital after fragments from an Iranian missile struck her head.

Lack of shelters is also a prevalent issue in some of Israel’s poorer Jewish communities in areas like the south of Tel Aviv.

A new survey conducted by Hebrew University found that 82.7% of Jewish Israelis support the attack on Iran – but 67.9% of Arab Israelis oppose it. Further to that, 69.2% of Arab Israelis reported feelings of fear over the strikes – with 25.1% expressing despair.

“Arab society feels neglected and left behind,” says Amit. “There are huge gaps in education and employment. There are huge gaps in shelters, in the existence of shelters.”

Adel Khatib, a municipal official from Tamra, says: “In the days since this happened, you can feel the anger.”

“We don’t get the basic needs,” says Khatib. “Most of the Arab communities, they don’t have community centres or buildings for culture, activities.”

According to official Israeli statistics, in 2023, 42.4% of the Arab population lived below the poverty line – more than double the proportion in Israel’s general population.

There have been attempts in recent years to close these gaps. In 2021, Israel’s previous government brought in a five-year development plan for Arab society.

“We were in the middle of a huge leap in social economic development, narrowing gaps in education, higher education, and employment,” says Amit.

But Israel’s current right-wing governing coalition, the most hardline in its history, has slowly reduced funding for that plan – redirecting the money elsewhere.

Some of these cuts came as the government adjusted budgets to fight the ongoing war in Gaza, which began in response to the Hamas-led cross-border attack on Israel on 7 October 2023, in which about 1,200 people were killed and 251 others were taken hostage.

“This government has been simply putting, you know, sticks in the wheels of this five-year plan, not making it possible to implement broad parts of it,” Amit adds.

“For the past year and a half, Arab society found itself between a rock and a hard place in the sense that on one hand, they’re suffering from the policies of the current government, and on the other hand, they’re seeing their brothers and sisters in Gaza and in the West Bank suffering because of the war,” he says.

Outside the ruins of the family home, Mohamed Osman, 16, a neighbour, says: “Everyone is angry and sad.”

Speaking of Shada, 20, he says: “She studied her entire life. She wanted to be the best. Her father is a lawyer, and she wanted to be like him. All of those dreams, just disappeared.

“They were the best picture of a happy family…When I imagine them, I imagine the pieces of them that I saw.”

At a vigil ahead of the funeral, dozens of community members gather, greeting one another with handshakes, sharing coffee and tea, and mourning quietly.

“The bombs do not choose between Arabs or Jews,” says Kasem. “We must end this war. We must end it now.”

Photographs by Tom Bennett